News & Articles

ZFC on CBS Sunday Morning, July 6, 2003

Robb Report, June 2014

National Treasures

Click on the page below to read the full article in PDF format.

San Francisco Chronicle, July 4, 2003

Open Forum: Symbols of Patriotism

Click on the page below to read the article in PDF format.

Presidio, San Francisco, June 13, 2003

Historic American Flags Fly High at the Presidio on Flag Day; Free Family Activities and Flag Center Exhibit Highlight June 14th Celebration

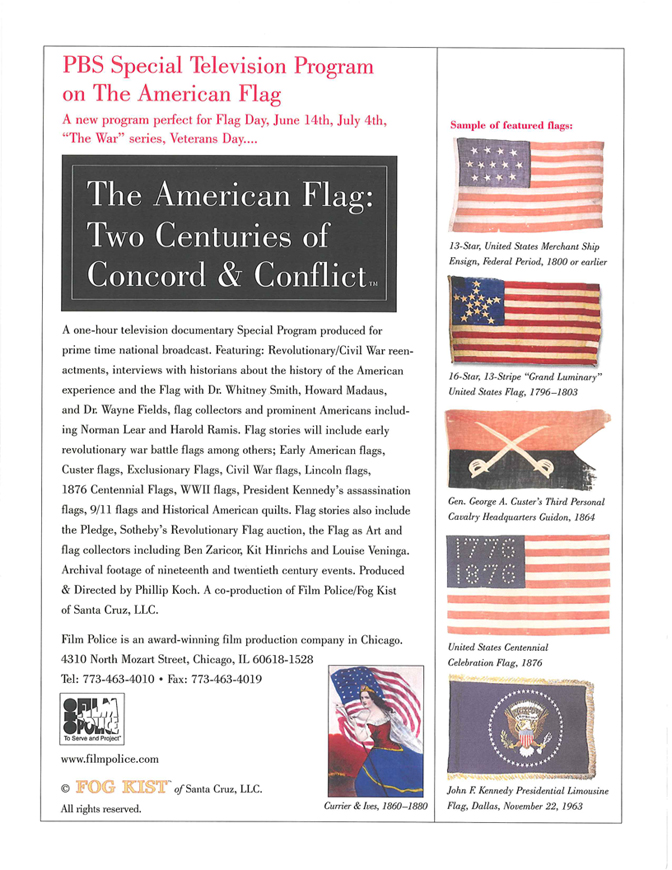

A collection of rare historic American flags will be raised in ceremony on Flag Day in San Francisco's Presidio as part of festivities surrounding The American Flag: Two Centuries of Concord & Conflict, an exhibit of more than 100 American flags and related Stars and Stripes memorabilia on view at the Presidio Officers' Club through July 31st. Admission is FREE.

Rarely made available for public viewing and even more rarely flown, these historic American flags will be hoisted up the Presidio's Main Post FlagPole:

- A 26-star U.S. flag dating from 1837, commemorating Michigan statehood;

- The 34-star "Grand Luminary" U.S. flag that was flown in mourning above the New York Central Railroad Station at Albany on April 26, 1865, when President Abraham Lincoln's Funeral Train stopped there on its journey to Springfield, IL.

- A replica of a vintage 1770's U.S. "Continental Colors," measuring 30 feet in length;

- A 35-star U.S. flag bearing the motto "Our Policy the Will of the People"; and

- A 15-Star, 15-Stripe replica of the Star Spangled Banner circa 1812.

Saturday, June 14, 2003 (ADMISSION TO ALL EVENTS IS FREE)

- Raising of Historic American Flags: 12 Noon-1:30 p.m.

- Family activities hosted by The Presidio Trust: 11:00 a.m.-1:30 p.m.

- Flag Center Exhibit Hours: 10:00 a.m.-5:00 p.m.

The flags are from the Zaricor Flag Collection of more than 1,500 flags and related items collected through the 32-year effort of Ben Zaricor, founder of Good Earth(R) Teas. In cooperation with flag historians, experts and enthusiasts from around the world, Zaricor is working to establish a permanent Flag Center in San Francisco.

The American Flag: Two Centuries of Concord and Conflict marks only the third time flags from this internationally acclaimed collection have been publicly displayed. Sponsored by Good Earth(R) Teas, Pentagram and The Presidio Trust, the exhibit is open 10:00 a.m.-5:00 p.m. Thursday-Sunday, 10:00 a.m.-8:00 p.m. Wednesday (Closed Monday & Tuesday).

Presidio Officers' Club, 50 Moraga Avenue (Arguello Gate) at the Presidio San Francisco

Rolling Stone Magazine, May 15, 2003

The Flag - Who Owns Old Glory?

Click on the cover below to read the full article in PDF format.

Indivisible

Wayne Fields

A speech given at the opening of the exhibit The American Flag: Two Centuries of Concord & Conflict, at the Presidio's Officers Club in San Francisco, California, January 12, 2003.

The founding fathers defined one of the most complicated plot lines that was ever assigned to a people to enact and to explore, and they did it in ways which I don't think they fully understood or to some extent ever hoped would work out successfully. They had a kind of simple but contradictory commitment that a people could somehow be both one and many. We carry that motto around on our coins — so convinced are we of its sacred nature — that says we are, somehow simultaneously, plura and unum.

The founders were not calling on us, as the leaders of other nations had, to become one from what had been many or to break apart and become many from what had been one. The plot line they designed was one in which we would be one and many at the same time. That we would somehow be able, as the Declaration of Independence insists, to define ourselves out of a fiercely suspicious nature built around our notion that individual rights take the highest priority and our commitment to affection as made in the opening line of the Constitution that we the people — and not the states, as the Confederation had imagined it — we the people are committed to a more perfect union.

The tension between those two parts of our heritage is acted out in the flag. The story that we see in the stripes and the stars is about the aspiration (and, often enough, about our failure to obtain it), to somehow carry that story forward into the demands of our own time. No design firm in America would come up with this flag. You can hear the criticisms — It's much too busy. Rectangles inside rectangles? — I don't think so! Stars next to stripes? And those colors! The busyness of it is because it is trying to retain the multiplicity of America in a single symbol. The fact that it has constantly been changing on us, reforming itself with the addition of states, and (I would argue) that through those same statements of transformation, changing in terms of the addition of cultures, addition of rights, addition of understanding of one another. All this has been extraordinary testimony to the persistence of an idea that, according to conventional wisdom, now as much as in the time of the founders, simply will not work.

As we see more and more how the new republics that were formed after the fall of the Soviet Union become increasingly convinced that only communities of likeness can be one, that only communities in which difference has been eliminated can be successful as communities, we begin to understand the depth of the importance of our struggle with this story line and also the extraordinary commitment it has taken to carry it this far and to move it ahead.

I will skip any elaboration of that beyond saying that the place where I find it most interestingly expressed was in the recent exposure that we've had in the excitement of flags in the aftermath of 9/11 when they were flying everywhere and commentary was being written about that display of patriotism in every major city of the United States.

I was not in a major city most of that time. I was traveling around a part of rural Missouri and southern Iowa where very few people or media and politicians go by the farms. Very few of those farms are prospering now, yet a group of people that has become as impoverished and as marginalized as many people in our inner cities had flags flying there for nobody in particular to see, since nobody in particular ever drove by those farms.

One of them happened to be the farm of an acquaintance of mine. I asked him — a very crotchety man who makes me look pleasant by contrast-why he had done this, since he literally lives on a road that nobody else takes. What he tried to explain was that for him it wasn't a sign of defiance. He didn't expect any Al-Qaeda to suddenly jump up in a soybean field. It was the only way he had of showing solidarity with the people that he had never seen before but considered his countrymen. He has never been to New York, has no aspiration to go to New York, and wouldn't care much for New York if he ever got there. But New Yorkers were for him, like the rest of his more immediate dysfunctional family, people that were to be cared for and loved in spite of himself and in spite of themselves.

The flag has become not something we just say to the rest of the world. The flag is something we say to one another — and in my friend's case, to himself — about the deepest and profoundest commitments that make us a people. We understand that the symbol of our unity is also the symbol of our exclusion in crucial moments. It is tremendously important to go back and look at photographs of domestic strife, domestic demonstrations in every generation, to see that the flag is always there. That the suffragettes are waving it at the beginning of the century, that it leads the demonstrations at Selma and at Montgomery, that there is a constant effort to claim it in its fullest and most inclusive terms by people who have often been excluded in every other statement of who we are.

For me the great loss-and I have a jaundiced view of this because when "one nation under God" was added I had been saying the Pledge of Allegiance in school for about ten years already and had to learn it again or look like an idiot every time if I did not put in "under God" — was this: as important as that phrase was which the Baptist minister who wrote the original Pledge of Allegiance did not see the need for, the word it shouldered aside was indivisible.

Whatever God has to do with us and thinks of us, our security and real strength is only as great as our commitment to one another, and only so much as we believe that in some important way these diverse people that we have come to live among are people who can make us feel more secure and more at home than people who might be precisely like us. We are indivisible and we are indivisible because of a commitment to law and to justice and to each other.

This to me is the national story that the founders began to write but of course never imagined anybody finishing, at least not with a happy ending. This is the story that the flag contains in some important way. It is the story whose latest chapter depends upon what we write and whether we find it possible to write it together or whether we finally despair and let the story end.

War & Patriotism

Henry Berger

Remarks Prof. Berger made at the Presidio in San Francisco on the occasion of the opening of the American Flag Exhibit in January 12, 2003.

Patriotic language and symbols, in the words of historian Harry Fulmer, can be drafted "into the service of manifestly unjust causes." But patriotism, like many ideas worth talking about, is a double-edged sword. Patriotism can also be - and has also been - summoned to validate, rededicate, and recommit a national community to the values and principles on which the country has been becoming established. I say "has been becoming" established because I view it as a work in progress.

The labor, the effort, the sacrifice on behalf of liberty, justice, and equality was not finished at Independence in 1776 - nay, barely begun. Nor completed in 1865 with the abolition of slavery or climaxed in 1892 when the Pledge of Allegiance was written by Christian socialist Francis Bellamy, first cousin of Edward Bellamy, well-known author of the novel Looking Backward. Nor was the task finished in 1917 when America went to war, allegedly (and hopefully) to "make the world safe for democracy." Nor when William Tyler Page crafted the American Creed to educate the millions of immigrants who had come to America during the previous three decades - those immigrants who, among others, built the industrial capitalist order which made America by 1919 a great world power. The promise was not yet realized for workers who labored and fought for decent lives and recognition of their communal rights in the great labor struggles of the 1930s and the 1940s. Nor even finished with the accomplishments of the civil rights movements of the 1960s.

And surely not yet in our own time, when civil liberties embodied in the Constitution are being abridged - not for the first time in our history - in the name of security and when declarations of triumphalism and exceptionalism are heard in the land in the name of patriotic allegiance, when some Americans - knowing that we are the sole reigning world superpower - would display such hubris, dare we ask at this moment of crisis, in this war that we now face - may we ask with Matthew of the New Testament, "What shall it profit us if we shall gain the whole world and lose our own soul?"

The work of patriotic fulfillment as I am defining it is a continuing project. It is not static. It is not finished, nor probably will it ever be, nor should it ever be, so long as the promise of its values of freedom, justice, and equality for all is not served or is ill-served. Long ago a champion of equality, Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, reminded the country of this in an address in 1867 entitled "Are We a Nation?" at a time when the North and the South had only recently ended the carnage of civil war and were in the throes of the conflicted era of Reconstruction. He argued that the standards of patriotism to which Americans should aspire were high. Referring specifically to the flag and its stripes as the representation of patriotic virtue, he intoned: "White is for purity, red is for valor, but above all else blue is for justice. Whatever is done to advance these principles and to strengthen the Constitution as amended is patriotic. Whatever does not, diminishes and sullies the patriotic soul of the people - all the people."

A call to arms tends to distort and to simplify patriotic commitment. This was a flaw well recognized by John Quincy Adams, arguably America's greatest Secretary of State, in 1847 when the ex-President, then Congressman from Massachusetts, argued and acted against slavery and denounced what he believed was an unjust war against Mexico. Alluding to Stephen Decatur's toast in 1816 - "Our country:...may she always be in the right; but our country, right or wrong" - Adams sternly replied in his contrarian fashion, "Say not thou 'my country right or wrong' nor shed thy blood for an unhallowed cause."

We live in alarming and uncertain times. The nation would be ill-served if we did not scrutinize with the utmost care that which we are ignoring at home and abroad and doing so in the name of patriotism and the flag which represents it. Many, perhaps most of us, pledge allegiance to the flag. In 1965, in the midst of the black freedom struggle of that era, novelist and essayist James Baldwin asked, "Has the flag pledged allegiance to you? To all Americans?" As you tour this fine and exquisite exhibit of American flag history you might think about that and also these words about the flag and its patriotic meaning written by Henry Ward Beecher, brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe, in another moment of patriotic crisis: "A thoughtful mind when it sees a nation's flag sees not a flag only but the nation itself and whatever may be its symbols, its insignia, one reads chiefly in the flag the government, the principles, the truths, the history, which belong to the nation that sets it forth." The history, I might suggest, is for us - for all of us - to determine and to make it good and just for us, all of us, so that about the country and its flag we can rightfully raise our voices and joyously proclaim, as Marian Anderson sang it many years ago at the Lincoln Memorial, "Of thee we sing."

Henry Berger is Emeritus Professor of History at Washington University in Saint Louis, where he taught for thirty-five years before retiring June 30, 2005. Prior to that time he was also a member of the History Department at the University of Vermont for five years. Professor Berger taught and has written about American foreign relations and about discontent, dissent, and protest in America in the Twentieth Century. He is also the editor of A William Appleman Williams Reader (1994).

Whose Flag Is It, Anyway?

Ben Reed Zaricor

The American flag packs emotional wallop - a potent symbol viewed passionately across our political spectrum. Much of this passion appears to be rooted in highly personalized, possessive and often misguided perceptions of "ownership."

Many people feel so strongly about "Old Glory" that they are quick to draw lines in the sand and establish their own arbitrary dictates of what constitutes "respect" and what borders on "desecration" - a term itself suggesting something with religious, symbolic power, though the American flag was the first secular national flag. When someone, or some group, violates such artificial barriers, verbal and physical blows may follow as people rush to define and defend "their" flag.

Now we are in yet another phase of America's never-ending, often heated, public debate about the flag and how it "should" be displayed and treated.

That's why actions, for example, calling for an amendment to the Constitution to prohibit "desecration" of the American flag, go to the heart of our country's sense of liberty. I simply do not understand those who want to pass laws limiting our freedom of expression, which has been guaranteed by the Constitution for over two centuries. I do not hold, as others may believe, that our flag needs protection from its people.

Many Americans may not know that, from the Colonial period to 9/11, individual Americans have created and customized the flag independent of any governmental oversight. There is, for example, a long tradition of people incorporating the flag into their clothing. Some people also have added personal elements to their flags, such as writing their names along its borders. The Sons of Liberty added a snake and "Don't Tread On Me"; centuries later, others placed the "peace symbol" in the star field to deliver a specific message in the 1960s, and again in the aftermath of 9/11, the War on Terror and the War in Iraq.

The American flag, and what it symbolizes to people around the world, mirrors our nation's history-from the struggle for independence to today's role as the global superpower. And because no single group "owns" the flag, or ever has, its design and the materials it is fashioned from illustrate the creativity, whimsy and idiosyncratic realities that are embedded in our singular culture.

Because of the powerful emotions bound up in flags, and the fascinating stories tied to them, I decided to become a collector in 1969 when many of my friends would never have dreamed of collecting such things. At that time I saw a young man in a restaurant beaten for wearing a stars and stripes vest. That experience awoke in me a passion to learn the history of our flag, which I discovered was hidden in the old flags.

The creation of a national flag center would provide a permanent, year-round venue where people could view flag exhibits and learn our country's history through these old and torn pieces of cloth. It would provide a forum for discussion of the ideas that influence our character as a nation and a place to participate in spirited educational debates and programs. Today there is no place like The Flag Center where you can see the original flags that tell so much of our country's "sea to shining sea" destiny.

Our flag tells a story of diverse ideas, cultures, personalities, races and political persuasions. It is a story both of differences and of unity. The stars on the blue canton of the flag represent individual states and their union; it is perhaps the most vivid expression of our national motto, E Pluribus Unum - "Out of Many, One!"

It is our flag, not the flag from our government. It is something we use in our everyday lives to express ourselves and our political freedoms. When you look at these pieces of American history, you realize they were designed, made and used by people very much like ourselves. This flag belongs to us all.

Ben Zaricor, co-sponsor of the 2003 exhibition in San Francisco, The American Flag: Two Centuries of Concord & Conflict, began collecting flags in 1970 while a student at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. With his wife Louise and family, he has assembled more than 2,500 flags, quilts, and other flag related items in the Zaricor Flag Collection. A version of this essay was published in the San Francisco Chronicle on July 4, 2003.

The Star, Quarterly for the Members of the Star-Spangled Banner Flag House Association, Spring 2004

Grand Old Flags on Exhibit at the Flag House

Click on the page below to read the article in PDF format.

Rolling Stone Magazine, May 15, 2003

The Flag - Who Owns Old Glory?

Click on the cover below to read the full article in PDF format.

Indivisible

Wayne Fields

War & Patriotism

Henry Berger

Whose Flag Is It, Anyway?

Ben Reed Zaricor